In an era marked by escalating technological advancements, environmental crises, and intensifying cultural conflicts, the need for a transformative rearticulation of human values has never been more urgent. At the heart of this transformative quest lies a critical interrogation of our modes of existence, belief systems, and the economic structures that have come to define this period—not merely as the fulfillment of late-stage capitalism but as the logical culmination of its contradictions, a trajectory long recognized in critiques of imperialism and monopoly capital.

Our engagement with the world is too often confined within the narrow parameters of political economy, where even environmental concerns—issues that should fundamentally redefine our economic and political structures—remain subordinated to financial interests. This persistent framing reflects the hegemonic logic of capital, which demands that all aspects of life be mediated through market valuation and economic utility.

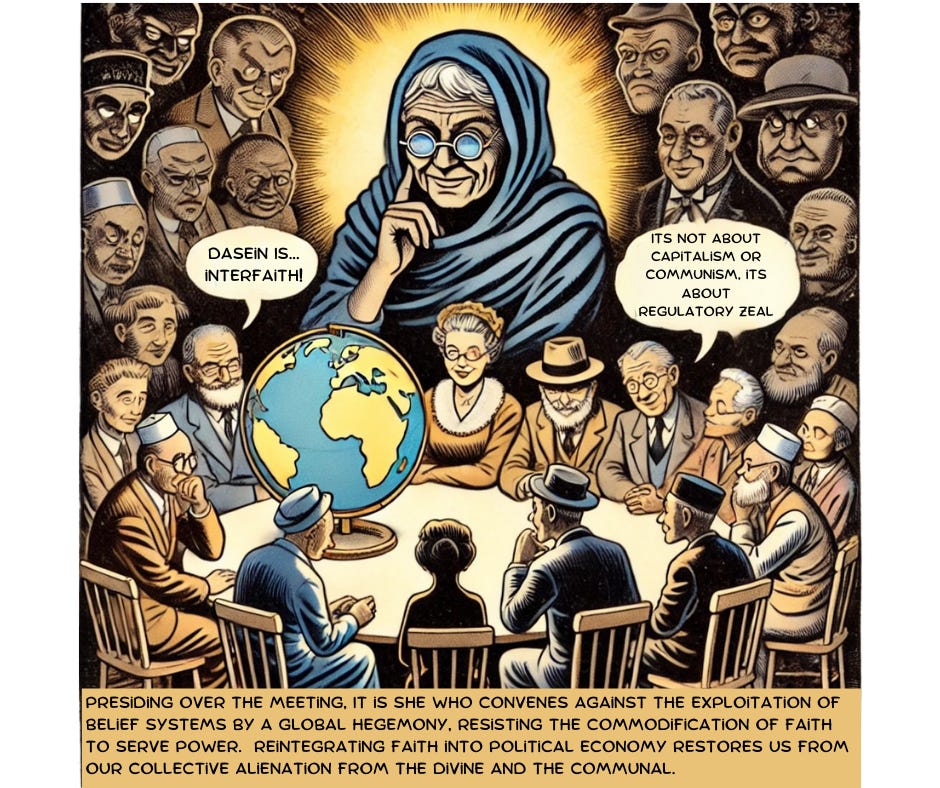

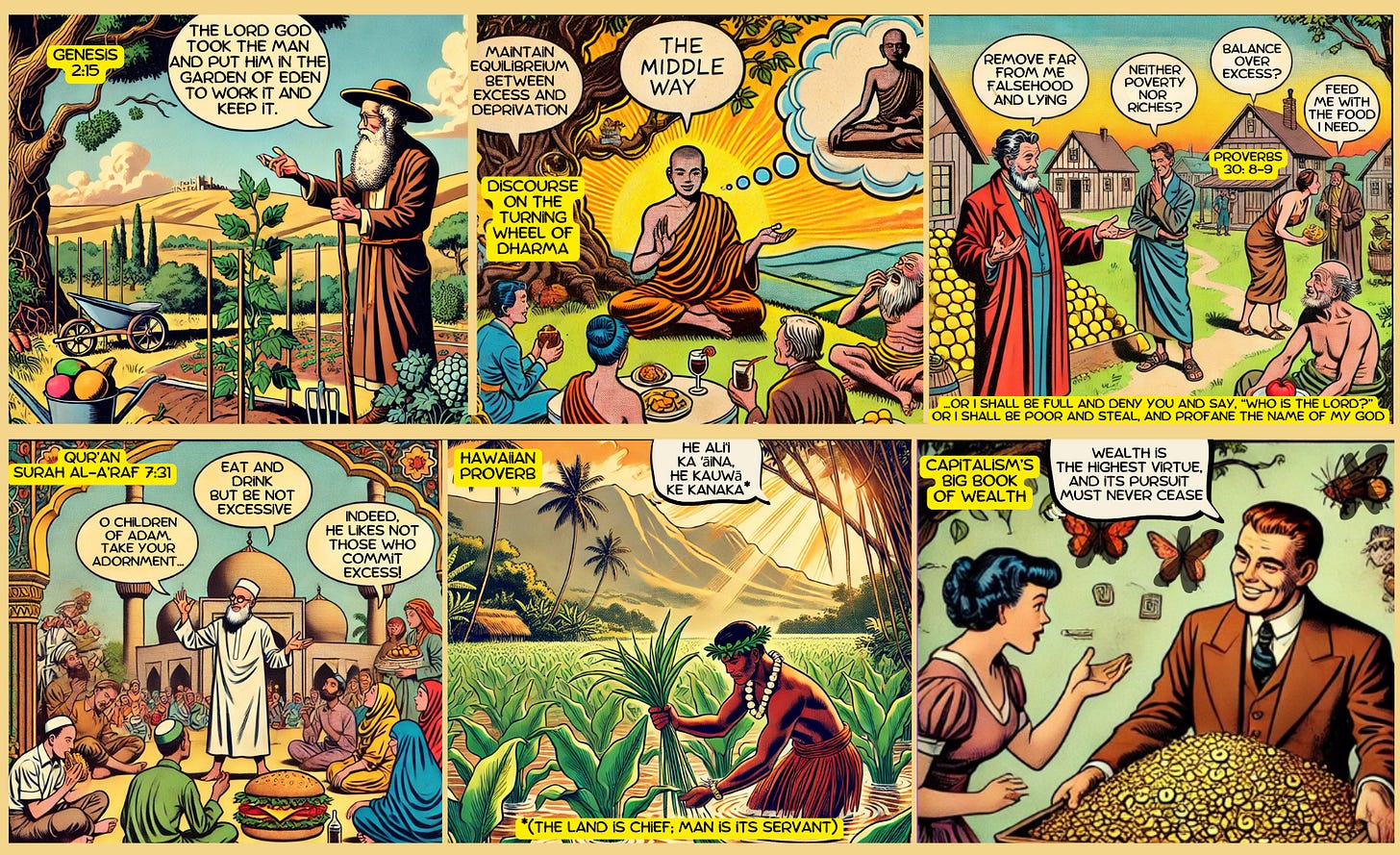

Yet, a critical omission in this framework is the role of interfaith engagement—not merely as a cultural or spiritual exercise, but as a structural force capable of counterbalancing the exploitative logics that define this era. Rather than an appendage to political economy, interfaith dialogue should be understood as a third pillar of human engagement, a necessary modulator that introduces ethical, moral, and cosmological considerations into the economic calculus. The systematic exclusion of faith from these discussions stems, in part, from its co-optation by power. Across history, organized religion has been instrumentalized to justify some of humanity’s most egregious crimes—genocide, slavery, expropriation, systemic fraud, and the violent dispossession of land and culture. This complicity has rightly drawn critique, but to dismiss religion entirely is to ignore its parallel tradition as a force for liberation.

Figures such as Jesus and Muhammad did not merely advance spiritual doctrines; they were radical social reformers who directly challenged the material and political structures of their time, calling for the redistribution of wealth, the upliftment of the poor, and the dismantling of oppressive hierarchies. Gautama Buddha, in his rejection of attachment to material accumulation and his emphasis on ethical living, laid out a framework for liberation that, while often depoliticized in contemporary readings, fundamentally disrupted the prevailing social and economic order.

Rather than allowing religion to be instrumentalized by capital or state power, interfaith engagement should reclaim its role as an emancipatory force. It must resist both commodification and dogmatic rigidity, positioning itself instead as a site of collective ethical reasoning—a space where economic and political decisions are scrutinized through the lens of justice, sustainability, and communal well-being. In a world where neoliberalism has normalized the commodification of life itself, the reintegration of spiritual and ethical dimensions into our economic models is not just desirable but necessary for survival.

Martin Heidegger’s seminal work, Being and Time, arguably offers the clearest articulation of “being,” echoing indigenous principles like the Fijian notion of Vakatabu—a philosophy of restraint and a “Whole of Life” sensibility. Indigenous epistemologies and spiritualities intertwine with Western humanist traditions, offering a potent counter-narrative to neoliberalism, Christian nationalism, and imperial domination.

The notion of spiritual warfare is deployed here not as a metaphor for conflict among differing belief systems but as a substantive framework for understanding the clash between humanistic, ecologically sustainable values and the destructive tendencies of neoliberalism. This article argues that our humanity, as encapsulated in the existential inquiries of Heidegger, has exposed the alienation inherent in our technological and economic regimes. Indigenous traditions and spirituality like Vakatabu offer a more integrated vision of being—one that is deeply relational, bound by place, and often attuned to Indigenous Peoples’ perceptions of the natural world.

But my friend, we have come too late. Though the gods are living,

Over our heads they live, up in a different world.—Bread and Wine (excerpt), Friedrich Hölderlin

I. Heidegger’s Being and Time: Revisiting Existence

In confronting the crises of our post-modern era—an age defined by hyper-financialization, ecological collapse, and the algorithmic mediation of existence—we must recognize that we are not merely passive subjects within these systems but existential beings whose fundamental orientation is toward ‘Being-in-the-world’. Heidegger’s Being and Time challenges us to move beyond the superficial distractions of technological modernity and late-stage capitalism, not through nostalgia or retreat, but through a radical re-engagement with authenticity, finitude, and collective responsibility. Rather than accepting the extractive logic of the present as an inevitability, we must actively reject this era’s defining conditions, not in the sense of regression, but in a conscious movement toward a future grounded in a deeper understanding of Being—one that recognizes the wisdom embedded in indigenous epistemologies, the ethical imperatives of interfaith traditions, and the necessity of a moral realignment with the world. If we are to navigate the spiritual and existential crisis of our time, it will not be through further immersion in abstraction, commodification, or hyper-acceleration, but through aligning to ways of being that have long resisted the totalizing force of capital. In this, indigenous traditions and interfaith ethics offer not merely alternatives but vital pathways toward a more just and ecologically attuned existence, reminding us that the future is not something to be optimized, but something to be lived, relationally and responsibly, within the fullness of Being.

Heidegger challenges the traditional metaphysical understanding of human existence by exploring the nature of Being (Sein) in relation to time (Zeit). Heidegger contends that the human mode of being—what he terms Dasein—cannot be understood apart from its temporality, its situatedness in a world of possibilities, and its intrinsic finitude. His analysis reveals that modern technological society, with its emphasis on efficiency and calculability, has led to a disconnection from a more authentic way of “being”—one that is engaged, reflective, and rooted in the world.

Heidegger’s critique has often been read through a lens that neglects non-Western modes of thought. His focus on authenticity and the search for meaning should resonate with many indigenous traditions, even if he rarely acknowledged the alternative epistemologies that arise from communities with long histories of living in close symbiosis with nature. In many ways, the existential project Heidegger set forth is incomplete without a critical engagement with indigenous knowledge systems—systems that do not see time as a linear resource to be optimized but as a complex tapestry of relationships and responsibilities.

Like in the excerpt from the Bread and Wine poem, Hölderlin acknowledges that the gods have withdrawn, but their presence is not entirely lost—they exist elsewhere, waiting. Western or Indigenous, our human experience resonates with traditions where our connection to what is sacred remains dormant until it is rekindled by those who remember.

II. Vakatabu: Indigenous Restraint and the Whole of Life

In Fijian culture, the notion of Vakatabu encapsulates a sense of restraint and renewal—a principle that is not merely about self-control but is an ethical mode of being that governs interpersonal and environmental relationships. Vakatabu is imbued with the understanding that life is not an endless accumulation of resources or experiences to be exploited for immediate gain but is a carefully balanced interplay of give and take, presence and absence. This principle is directly antithetical to the consumerist ethos valuing accumulation and expansion at the expense of long-term sustainability and relational well-being.

Vakatabu leads communities to adopt a “whole of life” perspective—one that sees economic activities not as isolated transactions but as embedded within a broader ecological and spiritual matrix. In this light, ecological accounting emerges as an indispensable tool. Unlike conventional economic accounting, which focuses narrowly on monetary transactions, ecological accounting acknowledges that human well-being is intricately linked to the health of the environment. By integrating the valuation of biodiversity and social relationships, ecological accounting—what might be termed “intemerate accounting”—offers a more comprehensive measure of prosperity, one that is aligned with the principles of Vakatabu.

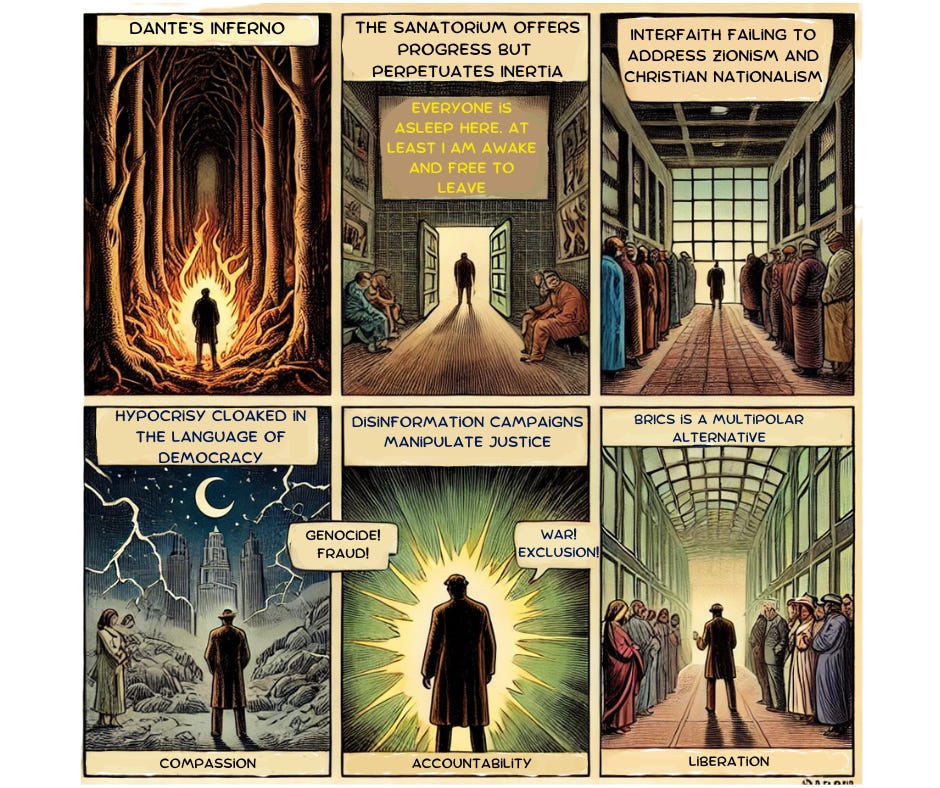

III. Spiritual Warfare: Hegemony, Faith, and the Political-Economic Struggle

The contemporary global landscape is marked by what can be termed as “spiritual warfare.” This struggle is evident in the contestation between ideologies that seek to impose a singular, often hegemonic, vision of humanity. On one side, we find the resurgence of Christian nationalism and contemporary Zionism—ideologies that not only claim divine sanction but also impose a rigid, often exclusionary, framework of belonging. This is evident, for instance, in the symbolic inscription of “In God We Trust” on the US dollar—a practice that intertwines religious iconography with the material power of a global reserve currency. Such gestures are not benign; they reflect an attempt to imbue economic transactions with a particular moral and theological order, one that reinforces nationalistic and imperialistic agendas.

Conversely, indigenous spirituality offers an alternative narrative—one that like interfaith, locates itself in a specific sense of time and place, and resists the commodification of belief. Indigenous traditions, with their totemic sensibilities and holistic understandings of the cosmos, challenge the reductionist worldview that underpins the neoliberal economy. They remind us that spiritual and material realms are deeply intertwined, and that the valorization of economic growth at any cost inevitably leads to environmental degradation and social dislocation.

The concept of spiritual warfare, then, might be understood as a struggle for the soul of society—a contest between a legacy of colonialism and imperial power, which exported a narrow, profit-driven view of existence, and a multiplicity of traditions that honor the intricate, interdependent nature of life. In this context, the battle lines are drawn not only in the economic or political arena but also within the realm of belief, where indigenous practices offer both resistance and an alternative model of living.

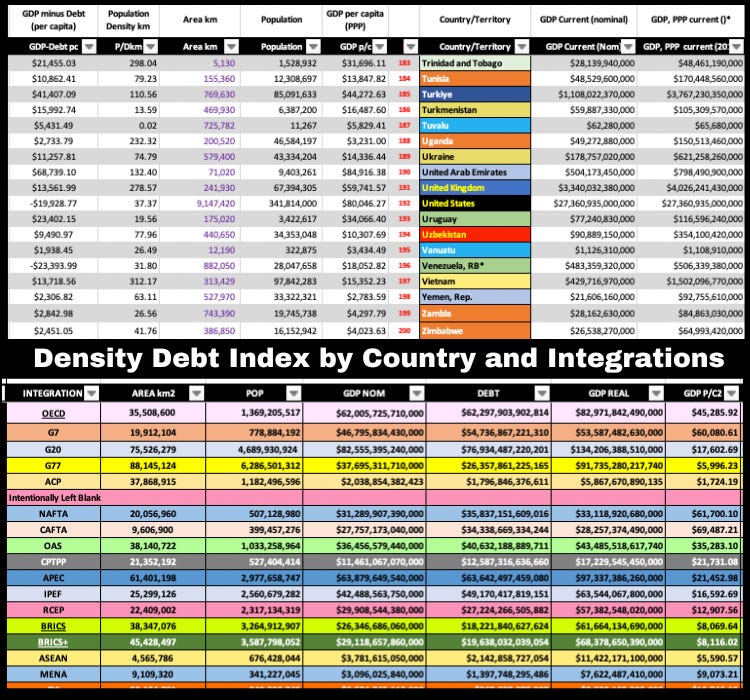

IV. Ecological Accounting and the Well-Being Economy

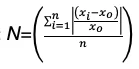

At the intersection of ecological accounting and indigenous spirituality lies the promise of a radically different economy—one that measures progress not in terms of GDP growth but in terms of well-being, environmental health, and social justice. The concept of “intemerate accounting” captures this alternative vision. By treating well-being as a modulator for economic performance, intemerate accounting challenges the dominant paradigm that equates value solely with market transactions.

This approach calls for the rearticulation of economic metrics to include non-market values such as ecosystem services, cultural heritage, and community resilience. It echoes the concerns raised by critics of natural capital valuation, who argue that monetizing nature risks commodifying what is inherently sacred and relational. Instead, by adopting a framework that privileges the cumulative value of our interactions with the environment, societies can begin to account for the true cost of economic activities, both in terms of ecological degradation and the erosion of cultural and spiritual practices.

Ecological accounting is thus both a technical and ethical project. Technically, it requires the development of new metrics, data collection methods, and regulatory frameworks that respect local data sovereignty and the principles of free, prior, and informed consent. Ethically, it challenges the prevailing logic of scarcity and commodification, offering instead a vision of abundance that is rooted in restraint—a vision that resonates strongly with the concept of Vakatabu. In this way, ecological accounting becomes a tool of resistance, a means to counter the hegemonic forces of neoliberalism and imperialism that seek to impose a one-dimensional measure of progress on a diverse and complex world.

V. Rearticulating Humanity: A Synthesis of Being, Restraint, and Spiritual Resistance

What emerges from this dialogue between Heidegger’s existential inquiry and the Fijian ethic of Vakatabu is a renewed conception of what it means to be human in the world. Heidegger’s call for an authentic engagement with one’s own being—an acknowledgment of the finitude and temporality of existence—finds a complementary echo in the indigenous insistence on living in harmony with nature and each other. Both perspectives challenge the relentless pursuit of profit and technological mastery that characterizes the neoliberal ethos.

In the context of spiritual warfare, this rearticulated humanity takes on a political and economic dimension. It is a humanity that refuses to be subsumed by a market logic that reduces life to a series of transactions. Instead, it is a humanity that recognizes the intrinsic value of restraint, embodied in Vakatabu, and seeks to build an economic system that is both ecologically sustainable and culturally inclusive. This rearticulated humanism stands in stark contrast to the divisive ideologies of Christian nationalism and contemporary Zionism, which serve as tools of imperial domination and cultural homogenization.

The struggle to reclaim this vision of humanity is not without its challenges. The forces arrayed against it are powerful and deeply entrenched, drawing on centuries of institutionalized power and the persuasive allure of market-based ideologies. Yet, as the global community grapples with the twin crises of climate change and social inequality, the imperative to rethink our economic and spiritual foundations becomes ever more pressing.

In practical terms, embracing a Vakatabu-inspired approach to life and economics would involve a series of transformative steps. First, it requires a fundamental reorientation of our educational and cultural institutions to valorize indigenous knowledge systems and ecological literacy. Second, it calls for the democratization of economic governance, ensuring that local communities have a decisive say in how their resources and data are managed. Third, it demands the development of regulatory frameworks that transcend narrow market logic and instead promote well-being—a regulatory vision that is attuned to the principles of free, prior, and informed consent.

In this rearticulated framework, economic indicators would no longer be the sole arbiters of progress. Instead, a suite of metrics that capture the health of our ecosystems, the strength of our communities, and the resilience of our cultural practices would come to define what it means to thrive. Such an approach would not only mitigate the ecological and social costs of unfettered growth but also forge a pathway toward a more equitable and sustainable global order.

Conclusion

If late-stage capitalism is capitalism’s final form, its expansion into environmental data marks the last frontier of commodification—where not only land and labor but life itself is financialized. This is not just an economic struggle but a fight for the right to exist beyond capital’s dictates. The question is not whether we can work within these markets but whether we can resist them entirely. Rejecting the premise that nature’s value can be measured, traded, and securitized, we must reclaim reciprocity, collective governance, and ecological autonomy. Yet capitalism’s total enclosure signals its own existential crisis, creating the possibility for rupture.

Drawing from Heidegger and Vakatabu, we can envision a future where well-being, ecological balance, and cultural diversity replace profit as the foundation of society. The struggle to redefine progress—not by monetary gain but by the health of our communities and ecosystems—is a struggle for our soul. As we navigate a world of deep divisions and competing visions, the wisdom of indigenous traditions and existential inquiry reminds us that economic, cultural, and spiritual lives are inseparable. Recognizing this interconnection is key to transforming the very foundations of existence.

References

Heidegger, Martin. (1962). Being and Time. Harper & Row.

Levi-Strauss, Claude. (1966). The Savage Mind. University of Chicago Press

Vaai, Upolu & Aisake Casimira. (2024). The ‘Whole of Life’ Way: Unburying Vakatabu Philosophies and Theologies for Pasifika Development. PTC Press