on my substack:

https://onibaba.substack.com/p/through-the-glass-darkly

A critical and intemerate response to the UNFCCC COP 30, October 2025 NDC paper, “Nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement”

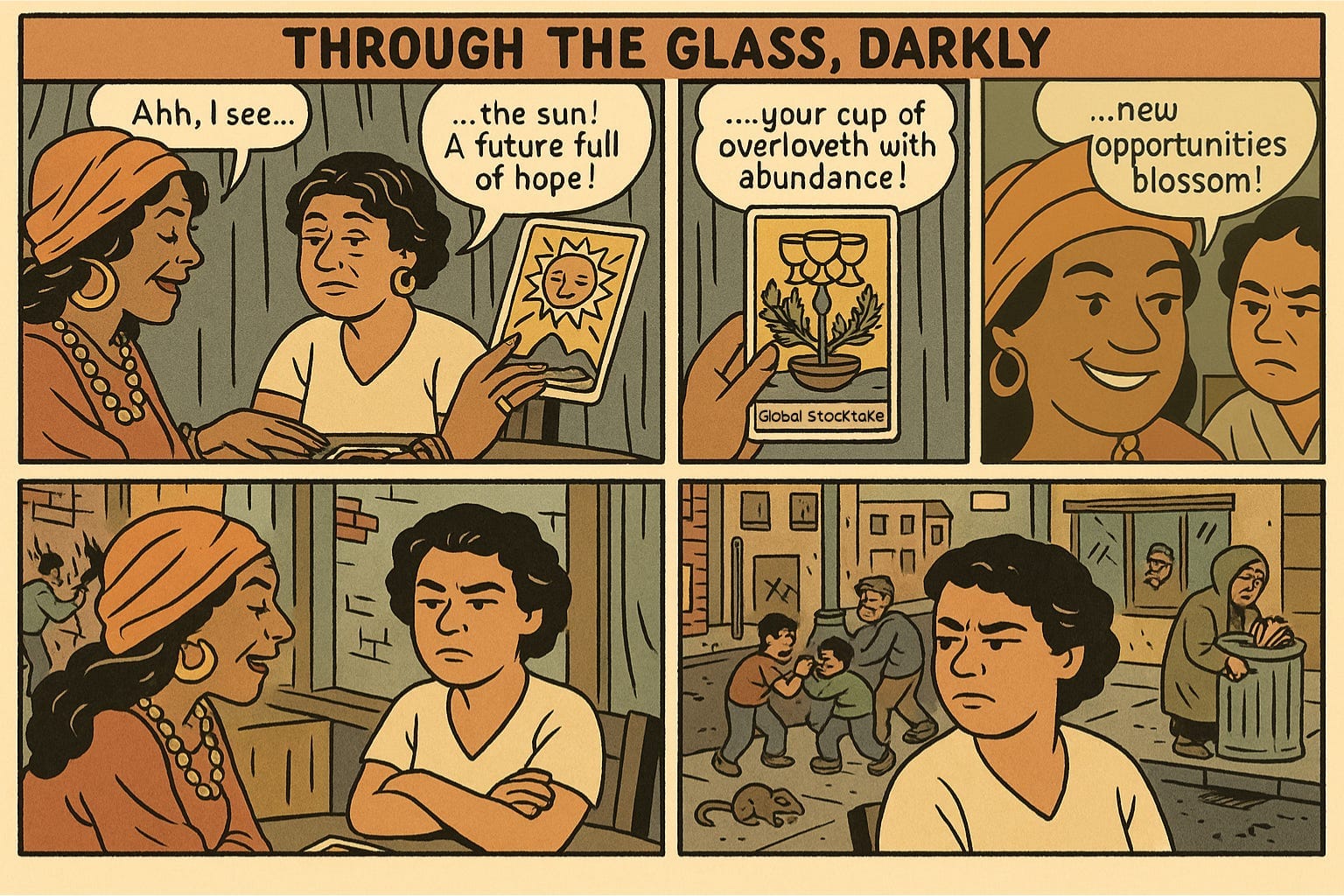

Through the glass, darkly, the world observes its reflection in the mirrored surface of debt. Climate finance presents itself as a race to save the planet, while concurrently dragging its feet through genocide, perpetuating, and provoking war and economic destabilization with countries and/or economies that don’t align with the targets of asset management. This image is refracted through an opaque medium in which debt and data have become indistinguishable currencies. The new economy of restoration—measured in bonds, credits, and blended instruments—rests upon the same arithmetic that has long commodified crisis. The result is a system that counts environmental virtue in units of liability, and it is within this accounting paradigm that nothing moves unless data are surrendered, standardized, and securitized by those who profit from accumulation. (See annex 1)

According to the report, 88% percent of Parties now quantify their financial needs, collectively estimating almost two trillion dollars to achieve their climate goals. Yet this number does not reflect ecological repair. It represents eligibility for loans, grants, and blended finance issued through international intermediaries, of which local communities have little access to developing or controlling. The calculation itself reaffirms dependence and development aid. The majority of states identify international sources as their principal means of implementation, while domestic finance remains marginal. For the 88%, what passes for cooperation is a hierarchy of access: to debt, to rating agencies, to the terms of disclosure. The poorer the country, the greater its obligation to make itself legible through data extraction.

With the expressed aim of decolonizing accounting methodologies, Intemerate Accounting rejects this conflation of valuation. Ecological accounting begins not with credit lines but with the veracity of local data. It treats knowledge as a reciprocal asset, not as collateral. Yet within the architecture of the Paris Agreement, data are produced for creditors, not for communities. Local biostatistics, resilience measures, and ecological inventories become the raw material for global climate finance. What is called transparency is, in practice, a kind of opacity. When trust is the real basis of reciprocity and exchange, the colonial system replaces that trust with its accounting methodology, using the language of data transparency to conceal the extraction that sustains it.

Their function is to verify compliance and maintain liquidity in funds administered by asset managers. If this is transparency, it is a ghost, a spectral transparency more aligned with the hauntology of capital, as I describe in detail in another post.

Measurement, Reporting and Verification (MRV) and Enhanced Transparency Frameworks (ETF) in the Paris regime are built to evidence compliance with Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and to standardize information for eligibility, disbursement, and review. The 2025 synthesis shows that 92 percent of Parties now describe domestic MRV systems, most linked to Greenhouse Gas (GHG) inventories and biennial transparency reports under the ETF; three-quarters describe formal tracking of NDC progress. These functions discipline how data is produced and shared, and they determine who qualifies for finance and on what terms.

But this is the crux of the sham.

MRV and the ETF assume that indigenous protocols and reciprocity schemes cannot be standardized, so they subordinate them to templates that serve creditors. Intemerate Accounting inverts this. Indigenous verification rooted in trust, consent, and continuous stewardship, I would argue, produces more accurate measures than distant audit frames because it binds evidence to responsibility. Any market that does not vest ownership, custody, and authorship of data in local practitioners will undervalue community resources and overvalue investor returns. Transparency without community control is spectral: an appearance of clarity that reproduces domination while claiming neutrality.

This “spectral transparency” obscures ownership and control of the underlying data, making it more performative rather than emancipatory. It only “appears” as openness while reproducing the power of those who determine what counts and who counts. That is the sense in which the visibility of MRV becomes ghostly.

The World Bank’s estimation of environmental data as a one-hundred-trillion-dollar asset is a fiction that reveals the depth of this confusion. It presumes that ecosystems can be priced in the same ledger as, for example, sovereign debt. The coincidence that global public debt approximates the same figure is not incidental. Debt and environment mirror one another: both are abstractions of life converted into obligations. The debt of nations sustains the liquidity of markets, while the data of ecosystems sustains the credibility of climate finance. Each exists to justify the other. The illusion of parity conceals the asymmetry of control.

To put things in perspective, the combined debt of the ACP countries is only around $4 trillion. But for many ACP countries, that debt is blood money, and it is the very real life and death to any genuine security that might be achieved if a decolonial accounting program were adopted. To be blunt, if the ACP were to tell the OECD countries that they need to pay off their $65 trillion in debt* before tackling their $4 trillion, how would the entire accounting matrix unfold so that all debt would be zeroed out? But here’s the rub: if the OECD economies continue to accumulate global environmental data, once again, the ACP, indigenous peoples, and alterity networks will be left at a disadvantage because, without owning their data, they will not be able to control intermediary markets and remain rentiers in ecological spaces they have stewarded for generations.

Imagine the United States and the OECD economies, holding the lion’s share of global debt, defining the terms under which ecological data are valued and exchanged. This is not hyperbole. Within the UN Statistical Division, the System of Environmental Economic Accounts (SEEA) is building a data reservoir that may seem benign, but when you consider that the only ones building this new accounting system are the OECD countries, with no substantive input from the Global South or from the real equity holders of global environmental data, we should not be foolish enough to equate benign with with benevolent. The architecture of SEEA encodes the same hierarchies that structure global finance. By positioning OECD institutions as the arbiters of ecological value, it transforms measurement into ownership and transparency into control. What appears as technical coordination is, in truth, the consolidation of data sovereignty within the very economies most indebted to the planet they claim to account for.

Moreover, U.S. military installations—both long-established and newly constructed under the pretext of national defense—are often situated directly above or adjacent to vital aquifers. Their presence is not incidental. These sites discharge classified chemical and radioactive pollutants into the very sources of freshwater that sustain nearby communities, while the data on contamination, remediation, and long-term risk remain hidden under security exemptions. This produces a layered form of control: polluting the resource, manufacturing scarcity, restricting access to environmental information, and consolidating that information into asset-managed databases. Within this arrangement, water becomes a dual commodity—first as a privatized physical resource, and second as data priced and traded through the same markets that determine financial derivatives. The secrecy of military pollution is not just an environmental crime; it is a data strategy that links ecological degradation to the governance of scarcity and the monetization of knowledge within the very same asset management houses that govern the different investment sectors in OECD economies. One of the dark sides of AI is how data computations, wielded by investment regimes, can turn data into trillions of assets, before the signatures providing our consent dry. (see annex 2)

So, within this context, who, really, are the external threats and actors?

Seen through this lens, the Global Stocktake is more of a ceremonial account—there is no material measurement, because there is no local market, no locally driven intermediary markets when it comes to, for example, warehousing, logistics, health care exchanges, risk pools and cooperative insurance, cultural knowledge cooperatives, mutual credit systems, procurement hubs, audit and verification clearinghouses, etc… Within traditional knowledge systems, these are all supply chain nodules that go back centuries, before neoliberalism, capitalism, and colonialism. (see annex 3)

The Global Stocktake, as understood within COP, is a perfunctory “take” without any stock.

They audit participation without altering the ownership of value. They translate local realities into universal indicators that sustain the global financial narrative. The act of reflection is itself commodified; the world is asked to gaze upon its moral image through the glass of data that others own. Nothing will be restored until that glass shatters.

Through the glass, intemerately, clarity emerges only through the grounded work of local verification, where value returns to those who produce and sustain it.

Intemerate Accounting proposes a reversal. To account intemerately is to remove the filter of debt and to see restoration as a process of restitution, but really an act of liberation, emancipation, and decolonization (LED). Value must arise from verified restoration, held within local custody, expressed in regional accounts that balance monetary factors with ecological variables. Data must serve communities first, not creditors. Only when communities control their information can finance cease to function as an instrument of enclosure and become a mechanism of reciprocity.

Through the glass, intemerately, we begin to see how reflection has been mistaken for truth. Debt has been treated as unavoidable, and data as unquestionable evidence. To see clearly requires stepping beyond the mirror of finance and the abstractions that mistake exposure for control. Clarity emerges only through the grounded work of local verification, where value returns to those who produce and sustain it.

Decolonize Accounting is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work with a cup of coffee, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Annexes:

annex 1. 1 Corinthians 13:12 teaches that our present knowledge is partial and mediated, “through a glass, darkly,” while full understanding comes only “face to face.” The Qur’an states the same epistemic limit in a different key: hearts can be sealed and veiled so that hearing and sight fail (Q 2:7; 17:45–46). Read against the Global Stocktake, these verses name a structural problem. Aggregated indicators promise vision, yet they filter reality through distant categories and institutions. What we see is a managed reflection, not a face-to-face account of restoration. An ethical stocktake would attend to the veil itself. It would replace mediated visibility with accountable proximity by centering local custody of data, consent, and community verification. Until these conditions hold, the Stocktake measures what it is designed to allow, and dismisses what the framework excludes.

annex 2. This captures the structural violence of data monetization: the conversion of information into speculative capital without meaningful consent. In the context of a decolonial accounting system, it exposes how AI operates not as a neutral analytical tool but as a multiplier of enclosure. Machine learning systems extract behavioral, ecological, and biostatistical data, standardize it, and feed it into valuation chains governed by asset managers. Consent, when it exists at all, is procedural—signed but never understood, automated within terms-of-service architecture.

AI, therefore, functions as an accelerant in the ongoing financialization of data. It processes and prices data. Once processed, local and ecological data enter global markets as synthetic assets—carbon credits, environmental derivatives, ESG portfolios—detached from their communities of origin. The transformation happens in milliseconds, yet its effects can endure for generations, as ownership over the data’s value migrates upward into investment funds while the consequences of extraction remain local, and that data builds value through the intermediary of data governance, creating a further division of accessing wealth.

In short, AI enables a new form of expropriation: an instantaneous capitalization of consent. What looks like computation is, in truth, the continuation of colonial accumulation through algorithms trained to interpret the world as collateral.

annex 3. In the early days of supply and exchange—before colonial borders and corporate law—trade was rooted in protocol, reciprocity, and mutual recognition. Markets were extensions of community, not instruments of extraction. People exchanged goods, knowledge, and labor through relationships governed by trust and custom. Security, storage, and translation of value were collective responsibilities, sustained through offerings or tithes that reinforced social balance rather than accumulation. These exchanges linked territories through mutual obligation, ensuring that value circulated without domination.

Colonialism broke that equilibrium. It replaced reciprocal trade with monopolized access, transforming markets into tools of exclusion. The colonized were barred from setting prices, issuing currencies, or defining value on their own terms. Markets ceased to reflect relationships and instead became infrastructures of control. The rhetoric of the “free market” masked the violence of dispossession.

Today, that structure persists under a new form of empire—data capitalism. Every act of communication, movement, and consumption is captured, quantified, and transformed into asset value. Our actions feed systems that convert behavior into capital. What was once overtly stolen is now silently expropriated through code. The tithe has become algorithmic: we pay it not with goods, but with our digital presence. To participate is to yield information that others own and monetize.

This condition, however, is not inherent to technology itself. Technology is neither liberating nor oppressive on its own. The distinction lies in governance. Some nations, such as China, possess the same computational capacities but deploy them under a model that asserts data sovereignty and rejects the Western doctrine of “data transparency.” That rejection is not about secrecy; it is about control. It recognizes that transparency, when defined by financial or geopolitical interests, becomes a form of surveillance masquerading as openness.

From the standpoint of Intemerate Accounting, the issue is not the use of technology but who defines its ethics and owns its outputs. Colonialism continues whenever data leaves communities without the full free, prior, and informed consent of the program or an understanding of how to access, manage, and restore equitable compensation. The alternative lies in restoring the principle that guided precolonial exchange: trust grounded in responsibility. Local data sovereignty reclaims that right, transforming technology from a means of extraction into a tool for equitable accounting, where value and information remain in the custody of those who create them.