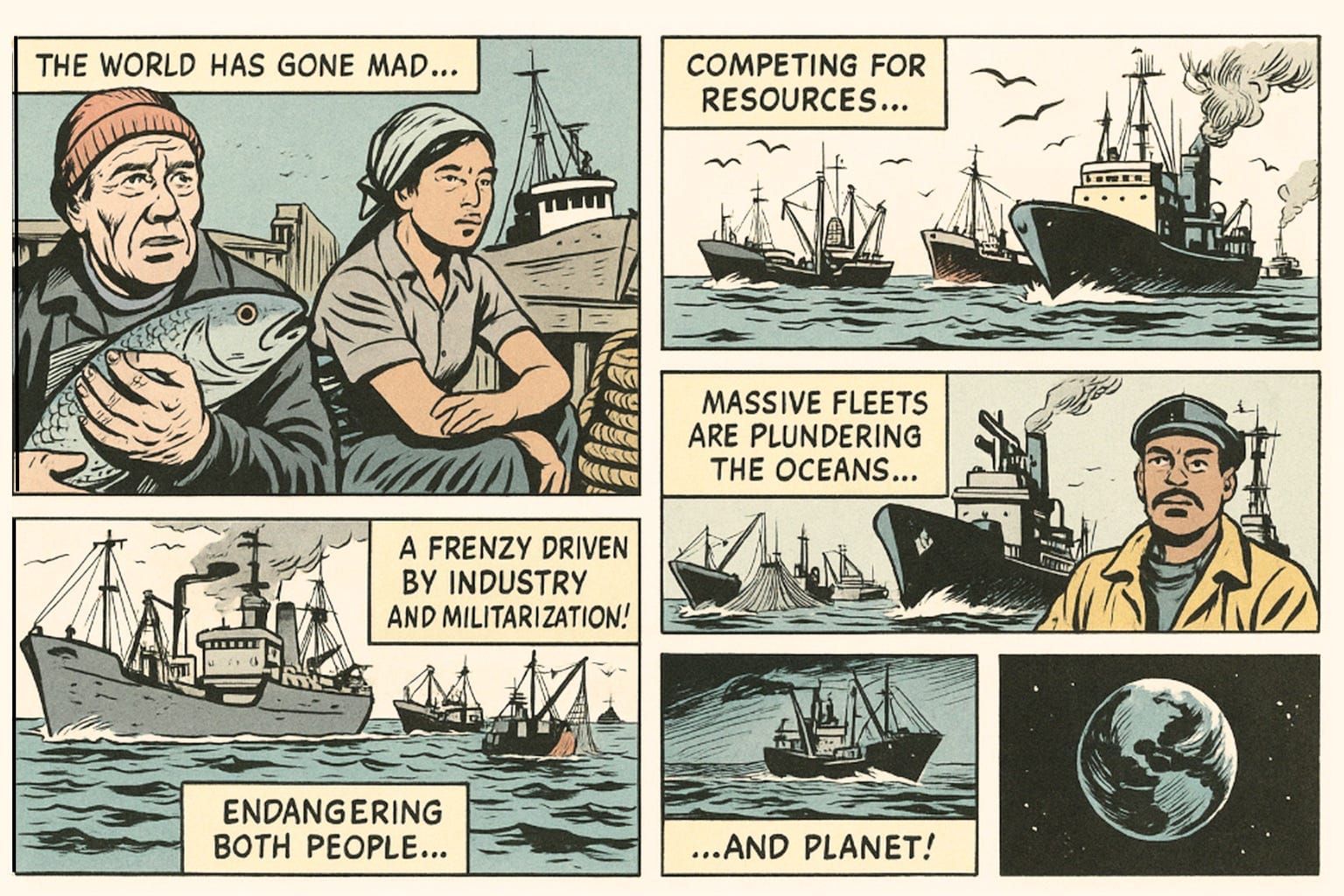

On April 17, 2025— the White House released two coordinated executive actions (see last week’s post), that together seeks to reshape the political, economic, and ecological future of Pasifika. The first, a presidential proclamation, Unleashing American Commercial Fishing in the Pacific, dismantles key protections within the Pacific Islands Heritage Marine National Monument (PIHMNM) (formerly PRIMNM), reopening these federally protected waters to commercial fishing. The second, an Executive Order titled “Restoring American Seafood Competitiveness,” reframes the national seafood strategy through a deregulatory, protectionist lens—cutting environmental oversight as an excuse to challenge foreign fishing competitors. While each action stands on its own, together they constitute a deliberate repositioning of U.S. ocean governance—away from preservation and toward a militarized industrial economy operating under the banner of national competitiveness.

The PIHMNM, once one of the world’s largest no-take marine sanctuaries, has been reclassified as a strategic economic zone. The proclamation claims that restrictions on commercial fishing within PIHMNM are unnecessary, citing the migratory nature of tuna and the sufficiency of existing environmental regulations—yet this justification collapses under the weight of its own contradiction: if the fish are indeed migratory and already managed under federal law, then the real purpose of reopening these waters lies not in ecological science but in advancing a strategic economic agenda. By invoking biological mobility to justify deregulation while simultaneously launching an Executive Order to reclaim domestic market dominance, the administration exposes its intent—not to protect ecosystems or correct legal redundancies, but to reposition U.S. fleets in a global seafood arms race.

This reclassification does not merely permit activity—it redefines what marine protection means. Under this new model, “conservation” becomes compatible with large-scale extraction so long as the activity is conducted by U.S.-flagged vessels under federally sanctioned management schemes.

ABNJ & BBNJ

From an ecological governance perspective, the rollback of protections within the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, coupled with the Executive Order on Restoring American Seafood Competitiveness (RASC), risks undermining ongoing international negotiations around the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in ABNJ (Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction), particularly those articulated in the emerging BBNJ (Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction) agreement under UNCLOS. While the United States has signed but not ratified UNCLOS, it continues to participate selectively in its frameworks, asserting maritime jurisdiction when advantageous while rejecting binding obligations. By unilaterally dismantling one of the largest no-take marine zones for economic competitiveness, the United States sets a precedent that undermines the credibility of multilateral conservation commitments. It signals that marine protection is conditional, politically malleable, and ultimately subordinate to national commercial interests—posing a direct challenge to the cooperative ethos required for effective high seas governance.

The justification used—that tuna and other pelagic species are migratory and thus not resident within protected waters—runs counter to the ecosystem-based management principles at the heart of BBNJ. It narrows the scope of conservation responsibility to territorial boundaries, disregarding the ecological continuity of species and ocean systems. Moreover, by prioritizing deregulation, fleet access, and trade enforcement, the U.S. action deepens the fragmentation of international ocean law, weakening the moral authority of conservation leaders while emboldening extractive states to reinterpret or erode marine protections. At a moment when the international community is seeking to ratify and implement BBNJ’s ambitious framework for marine protected areas, benefit-sharing, and ecological connectivity, the United States’ turn toward seafood nationalism pulls on the very thread that could unravel the fragile diplomatic consensus needed to steward the ocean as a global commons.

The Executive Order that follows completes the shift in tone. It abandons any pretense of ecological precaution, declaring that U.S. fishing capacity is being “crushed” by overregulation and foreign competition. It calls for the immediate suspension or revision of regulations that burden domestic fishing, directs federal agencies to identify overregulated fisheries, and lays out a seafood industrial strategy aimed at global dominance. In place of multilateral coordination or bioregional sustainability, we find a return to techno-nationalism, where market share, fleet expansion, and deregulation are the new pillars of marine governance.

From the perspective of industry, this is a consolidation of federal support for a handful of vertically integrated seafood corporations that already dominate U.S. commercial fishing. Companies like Trident Seafoods and Tri Marine (which operates global tuna fleets) stand to benefit disproportionately—not because of their ecological stewardship, but because they possess the logistical infrastructure, political clout, and access to capital needed to mobilize quickly. While the rhetoric of “seafood competitiveness” champions the small-scale, independent fisher crushed by distant bureaucracies, this executive order favors corporate consolidation under America First.

PNA

Meanwhile, in Pasifika, advancing RASC potentially undermines the region’s most effective fisheries governance body: the Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA). The PNA’s Vessel Day Scheme (VDS) is one of the only transnational models that successfully marries ecological restraint with sovereign economic benefit.

Built from the legacy of postcolonial overfishing, the Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA) developed the Vessel Day Scheme (VDS) as a mechanism to reclaim sovereign control over tuna resources in the Western and Central Pacific. Rather than selling access based on catch volume or open-ended quotas, the VDS allocates a fixed number of fishing days to each member country annually. These days can be used domestically or sold to foreign fleets—most often from distant water fishing nations such as the United States, Japan, South Korea, or China—through bilateral negotiations or regional agreements. The fees for these fishing days are not calculated based on the economic size of the purchasing nation but are instead determined by a minimum benchmark price and market-based dynamics, with some day rates reaching over $10,000. This model shifts power back to Pacific Island states by encouraging sustainable practices and maximizing economic return. It transforms the tuna fishery from a site of external exploitation into a foundation for local revenue generation and ecological oversight.

The United States pays for approximately a quarter of PNA revenue and the capturing of transboundary tuna outside the PNA is likely to diminish revenue to the Pacific Island Countries who have relied upon the cooperation of the large fishing countries. At this moment, Pasifika does not have a lot of options.

Former PNA CEO Transform Aqorau noted, “Climate and other environmental factors, an over-abundance of tuna stock depressing prices, or market forces out of the PNA’s control can all impact fishing in the western and central Pacific. Fishing tuna heavily every year will have an impact on the fishery…we need to guard against this.”

The PNA VDS does not merely regulate fishing—it asserts a different logic of value, rooted in place-based custodianship and inter-island solidarity. The United States, in reasserting commercial fishing in waters adjacent to PNA territories, bypasses this logic. It sets a precedent: that American jurisdiction trumps regional cooperation, and that the path to sustainability can be rewritten unilaterally, without consultation.

Freedom of Navigation

Overlaying all of this is the persistent shroud of militarization. The PIHMNM proclamation references the coordination with the Department of Defense, emphasizes “freedom of navigation,” and affirms the strategic mobility of the United States. While ostensibly about fishing, the language echoes U.S. naval posture in contested maritime regions—particularly the South China Sea (worth reading)—where commercial activity, environmental protection, and military mobility are often entangled. The fishing fleet thus becomes a proxy—an instrument of territorial presence and economic claim-making, operating in tandem with military imperatives. In this sense, the rollback of marine protections is not only about opening waters to industry, but about reaffirming jurisdiction, projecting power, and managing ocean space as a geostrategic asset.

WTO

The conflict between the United States and Pacific Island nations at the World Trade Organization (WTO) over fishing centers on North-South visions of fairness, sovereignty, and sustainability in global fisheries governance. It reflects deeper tensions between powerful distant water fishing nations and small island developing states (SIDS) who rely heavily on their marine resources for both livelihood and state revenue.

At the core of the dispute is the WTO’s ongoing effort to finalize rules that would curb harmful fisheries subsidies—particularly those that contribute to overfishing, overcapacity, and illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. Pacific Island countries, especially members of the Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA), have pushed for these rules to differentiate between industrialized nations with heavily subsidized distant water fleets and small island states with limited fishing capacity but sovereign rights over vast exclusive economic zones (EEZs). The U.S., while nominally supporting subsidy reform, has frequently advocated for broad rules that could also restrict the use of fishing subsidies by developing countries, including SIDS—undermining the special and differential treatment provisions that Pacific nations argue are essential to their economic development and marine stewardship.

The U.S. has further clashed with Pacific nations over access fees and management models like the Vessel Day Scheme (VDS), which monetize fishing days within EEZs. Washington has criticized the rising costs of access under PNA frameworks and, in some negotiations, has implied that such schemes function as de facto trade barriers. From the Pasifika perspective, however, these schemes are not subsidies but expressions of sovereign control over resources historically exploited by wealthier countries. Thus, Pacific Island Countries sees the U.S. position at the WTO as part of a broader effort by industrialized fishing powers to erode their autonomy, secure cheaper access to tuna stocks, and undermine regionally-developed systems of ecological and economic governance.

In essence, the conflict at the WTO reflects a deeper struggle over who gets to define sustainability, who pays for conservation, and whether ocean governance will be shaped by extractive globalization or by the rights of coastal and island peoples to manage their own waters.

Quota system vs Vessel Day Scheme

The other point I want to make about the brilliance of the VDS system employed by Pacific Island nations is that it offers a transparent and equitable model for monetizing access to tuna fisheries. This system not only reinforces local sovereignty but also guarantees that revenues flow directly to the states and communities that steward the resource. In contrast, the quota-based system often promoted by the United States and aligned with global commodity market practices introduces complex mechanisms of allocation, trading, and speculation. Quotas can be bought, sold, or leased—frequently consolidated by industrial players or financial intermediaries through Wall Street firms—driving up prices and creating barriers for small-scale and family fishers. Instead of direct and predictable compensation for access, quota markets tend to abstract value, turning fishing rights into speculative assets that privilege capital over community, and undermining the participatory foundation of sustainable fisheries governance.

And so….

Together, the proclamation and executive order is once again rendering the ocean as another domain of industrial potential and strategic calculation. The sea becomes frontier again—not in the mythic sense of unexplored abundance, but in the regulatory sense of contested jurisdiction, privatized access and exploitation.

In this moment, Pasifika is not just a battleground of fleets—it is a battleground of philosophies. Will governance be grounded in extractive sovereignty or in the co-development of ecological limits? Will access be determined by flags or by customary stewardship? The answers are not only legal—they are cultural, economic, and planetary. And they demand more than the unipolar objectives of proclamations or executive orders. They require a reckoning with the systems of power that have turned the world into theaters of profit and dominance, rather than realms of life and interdependence.

In contrast to the zero-sum logic of extractive sovereignty—what might be called the “last man standing” or “King of the Mountain” game played by the Western hegemon—the rise of BRICS, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and other frameworks of new multilateralism offer an opening to reimagine economic cooperation through a decolonial accounting lens. Within these shifting alliances, there is potential to construct a different formula—one that moves beyond GDP as a measure of extraction and towards accounting systems rooted in ecological reciprocity, reparative justice, and translocal stewardship. Just as the game of Mancala distributes value through cycles, foresight, and mutual strategy rather than domination, a decolonial accounting approach could redistribute both access and valuation by centering the rights of small island and coastal nations to define their own metrics of wellbeing. Rather than assigning price to fish alone, this model could weigh the cumulative labor of custodianship, the biodiversity of oceanic corridors, and the intergenerational knowledge embedded in customary marine tenure. Such a shift would not simply adjust policy—it would reconfigure the ontological terms of global trade, replacing conquest with coordination and turning extraction into interdependence.

It may not be tomorrow but the near future that holds the possibility of a new kind of cooperation. In that future we might finally abandon the myth that endless accumulation confers strength. And perhaps it will not come through the empires that claim to lead, but through the convergence of nations once marginalized—BRICS and its growing orbit—emerging not as rival hegemon, but as the slow, deep current of another logic entirely. Like the whale in Moby Dick, it may be this collective weight—massive, calm, indifferent to Ahab’s frenzy—that ultimately sinks Pequod. Not in vengeance, but in gravity. Not as predator, but as presence. We are the Whale.