The Covid-19 pandemic has tested the strengths and weaknesses of our global interconnectedness and its implications for our environmental, economic, and social well being. In particular, as the outbreak has spread we have witnessed in real time the limits of the global economy. While some economies were not only able to address their national needs, but simultaneously provide assistance to other countries, many western governments looked to private markets as the only route for addressing the needs of the people. The fact that some countries even weaponized the virus by withholding aid while maintaining sanction power can only be seen as an immoral affront to humanity. There is something very wrong with an economic system that places capital markets and the pursuit of profits in front of the global needs of human and environmental well being. Time and time again, neoliberalism has failed communities in need, and this includes large countries with immense multi-trillion dollar public debts that can never be repaid. Covid-19 may have triggered a financial collapse, but by no means was it the cause. Therefore Covid-19 is a wake-up call for regions to embrace another system if it is to coherently prepare for future stresses. The combination of western economic decline, environmental distress, the rise of the multipolar system, new 21st-century technologies, and now Covid-19 has created an unprecedented opportunity for global political and economic transformation for the wellbeing of our planet.

Indeed, we should see Covid-19 as a test for the inevitable global environmental catastrophe to come. From this perspective we can only conclude that relying on a failed paradigm is not the route to choose. In the Pacific, indicators of our vulnerability and dependencies are defined and measured against the priorities of the advanced economies that have historically ignored our Pacific identity and value. Typically, these economies emphasise our remoteness, our relatively small population and land area as liabilities for our developmental. Therefore, that fact that we have never participated in the global economy as equals has not been because of our lack of value or regional self-determination, rather the conditions for recognizing our value in the global economy has been overshadowed by commercial and industrial needs of the wealthy.

Unlike the advanced economies, who rely upon large militaries or industrial capacities, or western conceived notions of production and consumption as economic indicators, we in the Pacific have a long history of voyaging and customary stewardship that highlights the strengths of our vast liquid continent that are unaccounted for. Our shared rights for reciprocity and ecological well being should motivate how we account for the economy. If we believe that such alternatives are possible, then we should recall that GDP (the dominant way in which national economies are measured today) reflects nothing more than a choice over which indicators we want to prioritize. Currently the GDP system prioritizes production, consumption, trade and research, which remain heavily weighted in favour of advanced economies. But alternatives are not only possible, but necessary. For example, in Soviet-era Russia their MPS prioritised labour and transport to account for the interconnectedness of remote areas. The current global climate is ripe for a new paradigm shift”

There is an opportunity for the Pacific to prioritise its shared ecological value as an alternative measure of a regional economy. Through the United Nations Statistical Division, work is already underway to effectively value ecological indicators through the System of Environmental and Economic Accounting (SEEA). However, this is no automatic win for the Pacific, and indeed the SEEA has been compromised by competing national and corporate private interests.

At the global level, the objectives of the large institutions and big-brother economies are to privatise value and remove barriers to property rights over our ecological biodiversity. Furthermore, what started out as an international mandate to include environmental degradation and resource depletion into national accounting systems ended up as an industry-specific guideline that measures environmental resources (such as water) as a commodity valued under patterns of production and consumption. Within the region, UNESCAP has already attempted to introduce an ecological accounting framework in a manner limited to national water and waste accounts. These kinds of conservation and sustainable-use methodologies are designed to favor corporate investments and privatization regimes allowing the open-access paradigm that resorts to short-term exploitation on a first-come, first-serve basis. Except for the task of accounting for our ecological data, these kinds of environmental accounting mechanisms do not benefit the Pacific.

Rather, we have the opportunity to account for our shared ecological value—our literal Pacific Ocean of Data— is a tremendous resource. Just as OPEC was created to protect and regulate petroleum resources by setting the price of its oil, the Pacific too, with its ocean of ecological data can ensure that the value of our biodiversity is measured and accounted for in a way that is fair and commensurate with the size of our area, our population and our identity. This will require the political determination to confront upcoming challenges collectively, as one Pacific continent, through ecological integration.

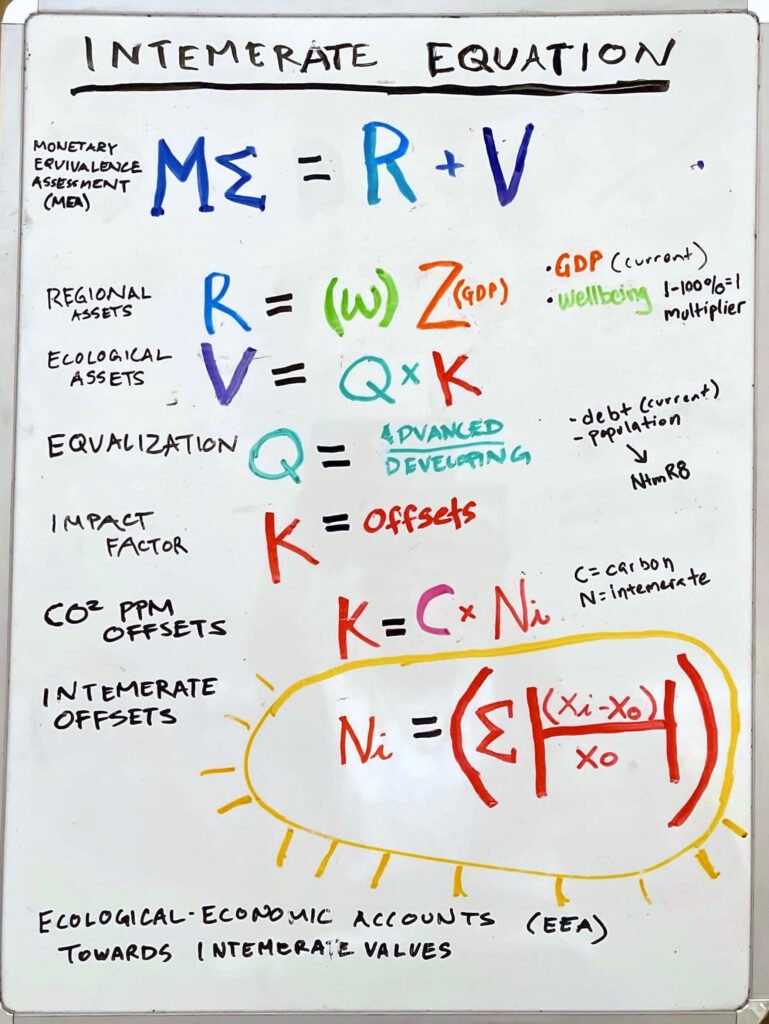

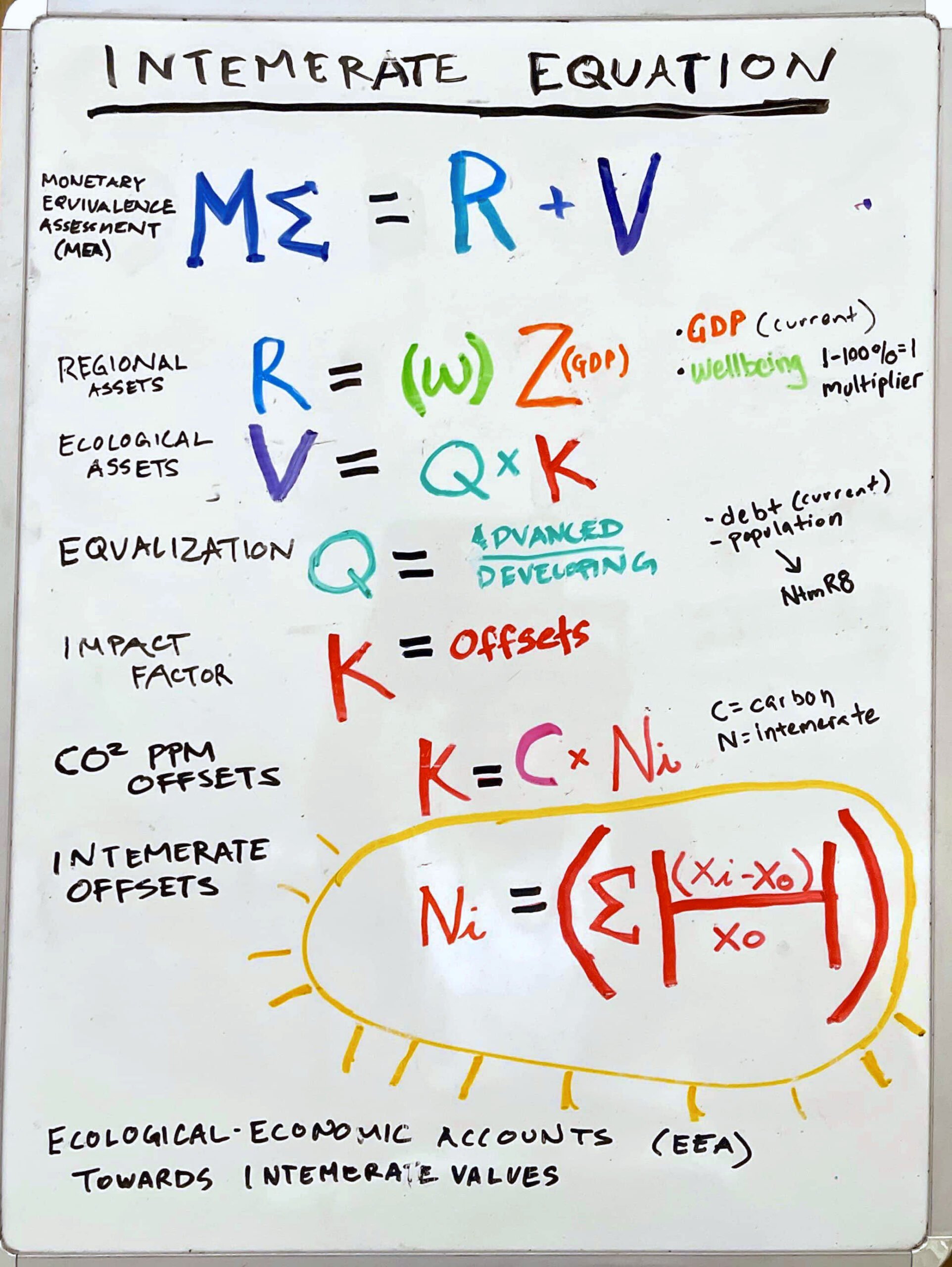

Recalibrating Pacific wellbeing through regional ecological integration will finally shake off the colonial/post-colonial yoke that continues to undervalue the region. The value of Pacific ecological integration can be maximised through what I term a Pacific-led Intemerate accounting framework. This framework will ensure that it is the Pacific that owns the data and that the value of that data is equitably measured for the protection and sustainability of its ecological resources. This will enable us to raise the economy of the Pacific towards a much higher per capita standard, measured to be on par with, for example, those OPEC countries. While the entire world has an ecological base that can be measured for sustainability (e.g., the 1987 baseline of 350ppm CO2), a regional ecologically integrated Pacific has the vast quantity and the ability – particularly if it were to be a first mover – to set the value of that data by negotiating an international market for ecological and social well being.