Pasifika should not be seen as a region waiting to be developed. It should be understood as a constellation of knowledge systems, cultural protocols, and ecological memory that can chart new economic futures. As climate finance, digital infrastructure, and geopolitical alliances shift toward a multipolar world, Pasifika communities are in a position to define a new basis for economic sovereignty—rooted not in extraction, but in stewardship. What lies ahead is not simply the protection of marine territories or the conservation of biodiversity. It is the articulation of data regimes, value systems, and accounting protocols that reorient wealth around reciprocity, care, and restoration.

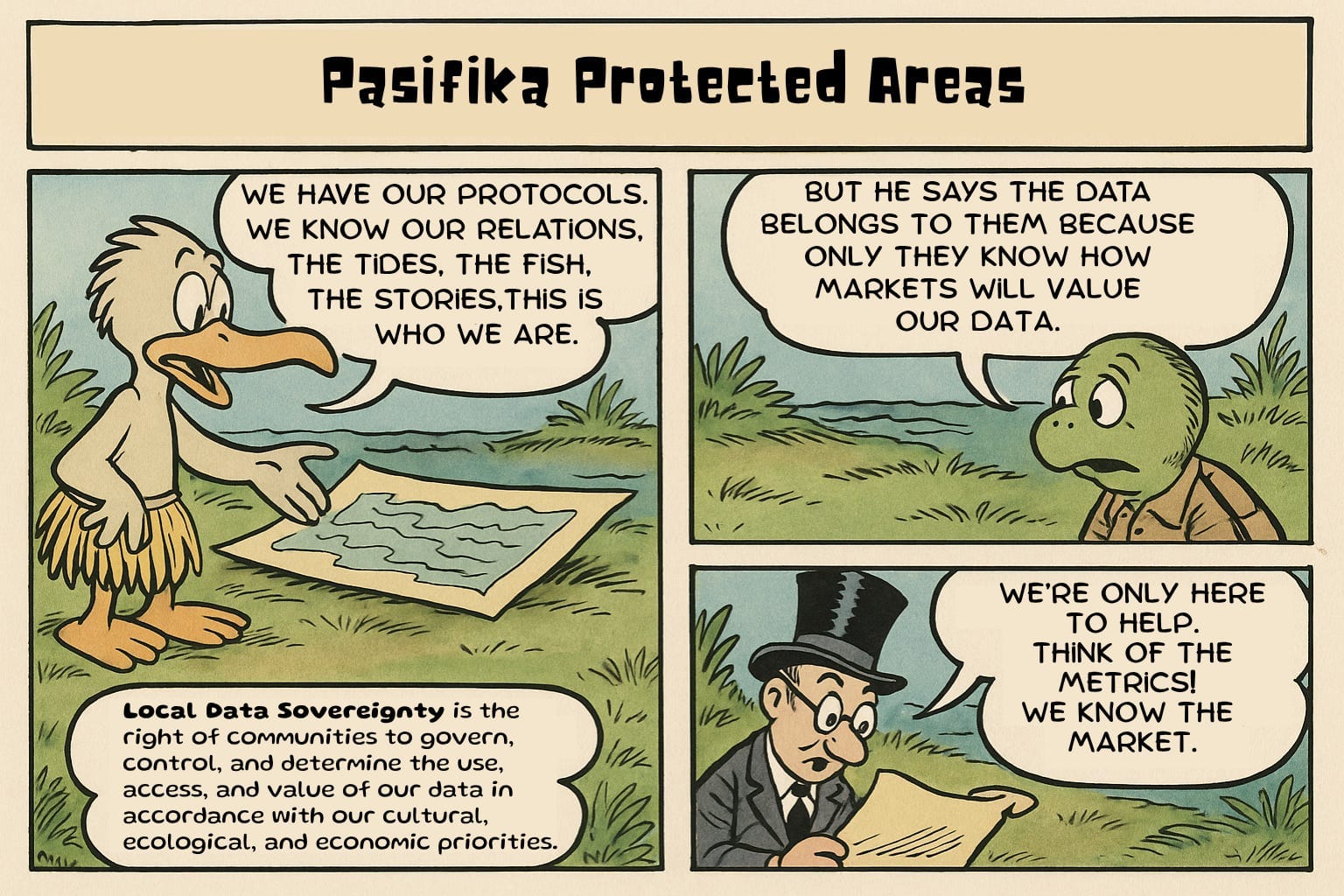

This is the potential of local data sovereignty. When communities control how their data is gathered, interpreted, and applied, they do more than manage their environments. They begin to shape the terms of exchange, define the metrics of value, and engage in economic practices that reject the financial abstractions imposed by carbon markets, biodiversity offsets, and speculative ESG instruments. Ownership of indigenous island knowledge—biodiversity, water systems, migratory patterns, seasonal flows—becomes the foundation of a new kind of economy. One that recognizes interaction, not accumulation. Stewardship, not speculation.

In this light, the 2008 Locally-Managed Marine Area guide by Govan et al. offers a valuable entry point. It laid the groundwork for community-based adaptive management (CBAM) in the Pacific, centering traditional knowledge, participatory mapping, and biological monitoring. The guide affirmed the importance of local engagement and recognized the role of custom in marine governance. But it did not yet consider that monitoring itself produces data capital. It did not imagine that the knowledge generated by communities could constitute an economy of its own. Tools that transect stakeholder matrices and seasonal calendars, for example, remain vital. Yet they are framed in the language of resource management rather than sovereignty. The data generated through CBAM is circulated to external institutions for conservation planning, not retained as a strategic asset by communities themselves. This is not a flaw of the methodology, but a limitation of its historical imagination. It now falls to the next generation to build upon that foundation and to reframe monitoring as a sovereign act.

This is what makes the announcement of the Melanesian Ocean Reserve by Ralph Regenvanu (Vanuatu) and Solomon Island National University so consequential. With over six million square kilometers of sea and island territories under a Pasifika-led protection, it promises not only to be the largest marine reserve of its kind, but the beginning of a political and epistemological shift. Led by the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, and aligning with a Kanaky EEZ, this reserve invites a reimagination of marine governance as both protection and jurisdiction. The opportunity not only challenges foreign extractive practices like Deep Seabed Mining. It is to turn environmental data itself into the terrain of regional autonomy by creating potential markets that value the stewardship of our ecological biodiversity.

This potential is amplified by the region’s geopolitical alignment. The Solomon Islands, through its participation in the Belt and Road Initiative, is positioned to develop regional data infrastructures that are not dictated by Australian or American frameworks. China’s orientation toward local data sovereignty for example, while certainly strategic, allows for a different kind of negotiation—one that does not presume default access to indigenous data or assume ownership of its applications. France, by contrast, and the European Union by extension, while advancing strong data protections internally, continues to extend colonial jurisdiction across the largest maritime zone in the world through its administration of Kanaky (New Caledonia), Tahiti (French Polynesia), and Wallis and Futuna.

To move beyond this structure requires not only policy realignment but educational transformation. The work being done at the Pasifika Communities University highlights how local indigenous accounting frameworks can be part of that shift. The development of curricula around intemerate accounting, local data markets, and translocal economies is a praxis of refusal and reorientation toward Pasifika relationality. In this program, students are learning to audit not in the service of compliance, but as a form of witness. They are defining metrics not to standardize value, but to restore relationality. They are learning to interpret data through reciprocal protocols that do not obey Western timelines, but follow seasonal rhythms, genealogical memory, and ecological responsibility. This is where Free, Prior, and Informed Consent becomes more than a procedural safeguard. It becomes the foundation of a data economy that respects the sovereignty of knowledge.

Intemerate accounting offers the architecture for this future. It does not quantify nature for pricing, but measures the quality of interactions between communities and ecosystems. It creates a framework where economic viability is inseparable from cultural integrity and environmental repair. Unlike GDP, which reduces life to output, or carbon credits, which monetizes damage, the intemerate equation recognizes that value must be situated within histories of care, displacement, resistance, and renewal.

To build on this foundation, we must recognize translocal data markets not as platforms for profit, but as circuits of solidarity. These are exchanges where communities share ecological insights and services, adapt strategies to shifting climate conditions, and hold one another in accountability and trust. They are not commodities but commitments, they are transactional transformations. What is exchanged is recognition.

This is the work ahead. Not to manage ecosystems within the constraints of existing frameworks, but to design new systems of accounting, valuation, and governance that emerge from the lived practices of those who have sustained these ecosystems for generations. The era of big conservation is nearing exhaustion. Its maps, its metrics, its mandates have failed to protect what matters most. What comes next must be authored from below, from within, from across the liquid continent of Pasifika where data is not simply a 21st-century resource to be accumulated by wealth extraction and private ownership by multi-trillion dollar asset managers like Blackrock and Vanguard, and other too-big-to-fail Assets under Management. Local Data Sovereignty prevents “colonialism-by-spreadsheet.”

Just as Marx described the shroud of capitalism settling across Europe, the Pacific has lived under its own veil of occupation, privatization, and enclosure. Foreign powers have laid claim not only to land and sea but to memory itself, covering the ocean of our ancestors and the futures of our children’s children, not just across our vast island network, but across time and the entire world. To lift this colonial covering is not simply to reject extraction. It is to restore visibility to all systems of knowledge and stewardship that have long sustained our regions. The threat posed by deep seabed mining, for example, is not just ecological. It reflects a deeper failure to recognize the value of our technologies, our protocols of care, and our capacity to define value on our own terms. Local data sovereignty allows us to navigate the global economy not as clients but as custodians of a shared oceanic future.

Deep seabed mining belongs to the imagination of a 19th-century economy, a world of imperial frontiers and accumulation through conquest. We do not need to live in that world. The valuation systems that animated empire—resource speculation, territorial expansion, extractive growth—cannot guide us through the ecological crises they helped create. The only valuation that now holds meaning is the resilience of the environment and the biodiversity that makes life possible. To ignore the technological imagination of Pasifika, to refuse the regenerative intelligence rooted in reciprocity and intergenerational care, is to abandon the very foundations of our history and community.

If our leaders cannot see the value of ecological guardianship, then that failure demands reckoning. This is not a policy dispute. It is existential. To support seabed mining is to uphold the most violent tools of colonialism: genocide, ecocide, slavery, theft, fraud, and dispossession. It signals surrender and collapse. Simply put, if our leaders cannot protect the sea, how can they protect the people who belong to it? To those who support DSM, they would have sold our ancestor’s bones for what essentially should amount to a sliver of a penny on the dollar. Think about that.